“Physically loose, and mentally tight.”

This was Arthur Ashe’s motto and mantra, which I came across while reading Ryan Holiday’s The Ego is the Enemy—a book I’ve read three times in the last year. It’s currently my second favorite book—it’s also my second favorite Ryan Holiday book—The Obstacle is the Way being my favorite.

I love many things about Ryan Holiday’s books (I’ll write more onHoliday in a column down the road), but the one thing I’d like to point out here is that I am never at a loss for things to read after reading one of his books. I always end up with several books I feel I have to read next.

So I went questing to find books on Arthur Ashe. His Days of Grace is in my queue. But I spotted Levels of the Game on Amazon. I had enjoyed John McPhee’s book on Bill Bradley’s basketball days at Princeton so much I decided to read that next.

So I went questing to find books on Arthur Ashe. His Days of Grace is in my queue. But I spotted Levels of the Game on Amazon. I had enjoyed John McPhee’s book on Bill Bradley’s basketball days at Princeton so much I decided to read that next.

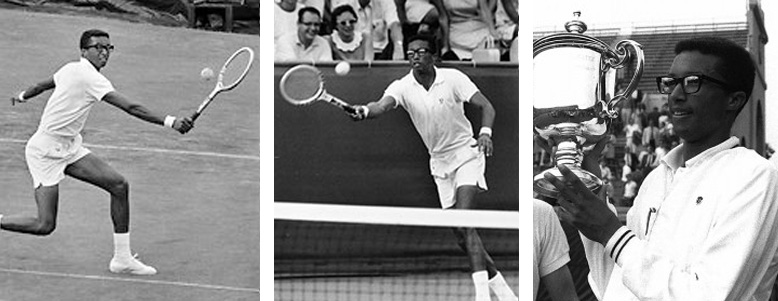

Arthur Ashe was in many ways the Jackie Robinson of Tennis. Except, as McPhee points out, there were many many good players in the Negro leagues that would have performed well in Major League Baseball, all things being equal. Which, of course, they weren’t. Jackie Robinson was chosen by Branch Rickey of the Brooklyn Dodgers because he thought Robinson was mentally tough enough to endure everything that would be thrown at him—the angry crowds, the racism, the calls that would go against him, the physical cheap shots that players would take at him. But Arthur Ashe, as a black tennis player, was peerless.

So like the boxer, Joe Louis, who was a master at keeping his emotions in check in the ring, Ashe kept his opinions about the umpire’s calls to himself. He channeled his energy into hustle and focus. Besides making him more fun to watch—not only are tirades not entertaining, they are are embarrassment to tennis, to sports, to all mankind—it kept his focus on what he could control, making him harder to rattle. He’s the opposite of bitchy players like Jimmy Conners or John McEnroe.

McPhee: “A person’s tennis game begins with his nature and background and comes out through his motor mechanisms into shot patterns and characteristics of play.”

Levels of the Game is structured around the 1968 U.S. Open semi-finals match between Ashe and Clark Greabner. The book follows the points of the match, adding in reflections by the players on a moment by moment basis, as well as biographical information about their upbringing, their families and the paths that brought them to this match. Graebner is the all-American boy type. Strong and hard-hitting, handsome, and well respected by people in tennis including Ashe, who was a friend and Davis Cup teammate. Graebner is given equal time by McPhee and seems likable and someone you might rout for—except maybe against Ashe.

McPhee: “A tight, close match unmarred by error and representative of each player’s game at its highest level will be primarily a psychological struggle, particularly when the players are so familiar with each other that there can be no technical surprises.”

It’s hard not to like Ashe. He’s an underdog, has obstacles to overcome, his play is described as fluid. His confidence fluctuates, and when things start going right for him, he begins taking chances with his shots. McPhee, writing about a turning point in the match: “Ashe is now obviously loose. Loose equals dangerous. When a player is loose, he serves and volleys at his best level. His general shotmaking ability is optimum. He will try anything.”

McPhee successfully interjects their memories next to his description of the game. He shows how a point here and a point there, how just a few inches, could have really tipped this match. But the main thing you get out of this book is how Ashe’s stoic attitude gives him his best shot to win the match, win the crowd, the respect of the judges, and even win the admiration of his opponents. He deals with details but he doesn’t sweat the small stuff. He controls what he can control, lets go what he cannot. As the match unfolds and Ashe loosens up and his confidence grows—its an amazing thing to read. “Physically loose, and mentally tight” is totally how I’d love to live my life.

After finishing Levels of the Game, I immediately reread A Sense of Where You Are, McPhee’s book about Bill Bradley’s senior basketball season at Princeton. First off, this is a really great basketball book. His descriptions of Bradley’s moves, the offense and defense of the game are precisely and eloquently done. He really zeros in on Bradley’s main strengths—discipline and concentration. McPhee describes how Bradley, not the most physically gifted athlete, deconstructs a move, his reverse pivot for example, breaks it into it’s component parts, then focuses on his footwork, then on the shooting motion, and finally putting it all together into a devastating, hard-to-defend package.

After finishing Levels of the Game, I immediately reread A Sense of Where You Are, McPhee’s book about Bill Bradley’s senior basketball season at Princeton. First off, this is a really great basketball book. His descriptions of Bradley’s moves, the offense and defense of the game are precisely and eloquently done. He really zeros in on Bradley’s main strengths—discipline and concentration. McPhee describes how Bradley, not the most physically gifted athlete, deconstructs a move, his reverse pivot for example, breaks it into it’s component parts, then focuses on his footwork, then on the shooting motion, and finally putting it all together into a devastating, hard-to-defend package.

“His creed,” McPhee writes, “which he picked up from Ed Macauley, is ‘When you are not practicing, remember, someone somewhere is practicing, and when you meet him he will win.’”

Here’s McPhee description of Bradley’s warm-up routine: “In Philadelphia that night, what he did was, for him, anything but unusual. As he does before all games, he began by shooting set shots close to the basket, gradually moving back until he was shooting long sets from 20 feet out, and nearly all of them dropped into the net with an almost mechanical rhythm of accuracy. Then he began a series of expandingly difficult jump shots, and one jumper after another went cleanly through the basket with so few exceptions that the crowd began to murmur. Then he started to perform whirling reverse moves before another cadence of almost steadily accurate jump shots, and the murmur increased. Then he began to sweep hook shots into the air. He moved in a semicircle around the court. First with his right hand, then with his left, he tried seven of these long, graceful shots-the most difficult ones in the orthodoxy of basketball-and ambidextrously made them all. The game had not even begun, but the presumably unimpressible Philadelphians were applauding like an audience at an opera.”

Both books transcend a sports book categorization. The sport parts are precisely written and are informed by the biographical, psychological, philosophical aspects of the stories. These are books that a sports curmudgeon could enjoy. Finally, Arthur Ashe and of Bill Bradley are humans you can learn from. If you could work toward what they were really amazing at—discipline, focus, being fluid in the moment—you’d totally be a more effective, more completely realized human being. And your backhand or hook shot would be vastly improved.