It’s February and Milan has been growing colder as the month plods on. My daughters have the week off school, so we’re taking our first trip to Africa, our first trip south of the equator.

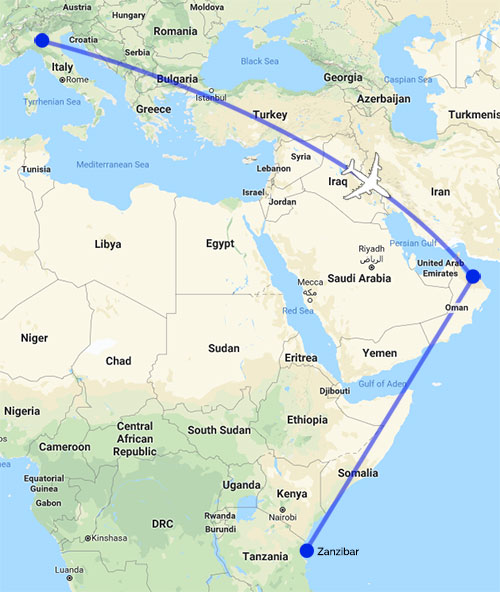

We are flying red eye. First to Oman, then to Zanzibar—14 hours door-to-door. We arrive at dingy, chaotic, well-named Malpensa airport, and immediate make for the Oman Air check-in counter. The tickets are checked. Our suitcases are on the belt.

The agent, unfortunately, has detected a potentially fatal problem.

The girls are flying with their German passports which expire in five months. We did not bring their American ones—it seemed unnecessary to bring an extra set of them. But Tanzania, which Zanzibar is politically part of, does not allow travel with passports that expire in less than six months. No one can tell us why.

They are checking into this. The Supervisor appears, is briefed. They are minors traveling with their parents for only a week—they’ve ok’d this before, we are told. He disappears. Minutes later, the agent is on the phone. She tells us her supervisor has left messages with a Tanzanian government official. No one knows if we can expect a timely answer. This confluence of bureaucracies does not bode well.

In the meantime, we call our housesitters, and hatch a plan to put the American passports in a cab and have them driven to us. The trip would take an hour, so there is barely enough time, but we’re prepared to pull the trigger on it.

At least one day of our vacation is on the line. The girls find some seats and distract themselves with their phones. My wife and I exchange glances. There is nothing we can do. After thirty tension-filled minutes, the supervisor appears and gives us the thumbs-up. Yes, you can go. Yes, the suitcases will make it on board. There is relief, but now we need to be efficient, and there is no time for dinner. This is not great as my daughters will refuse all airplane food sight unseen, on principle.

At the gate, we realize that in the chaos of getting to the gate, one of our government-issued yellow fever authorizations has disappeared. A thorough looking-through of the bag does not produced it. We decide to push on anyway. There was some ambiguity about whether they are necessary. We’ll see.

Finally in my seat, I relax and assess the possibility of sleep on this flight. My guess: Low to non-existent. There are USB ports. Good. Lots of movies and television shows. Whatever. I get out my kindle.

Seven hours later, we arrive in Oman. We get hummus plates and chicken burgers from a chaotic, fast food place, then head to the gate. We are stopped again for the same reason—passports expiring in five months. The agent phones her supervisor. We explain that her colleague in Milan phoned ahead and that it was okay. She says we must wait.

After twenty tension-filled minutes—boarding closer and closer to closing—the supervisor shows up. She explains the situation. He says it’s fine and waves us on. She tries to explain again. He repeats his response and we are allowed to board.

Now seated, we are relieved, but the plane is smaller. The seats are more closely jammed together, and do not tilt back. It’s 6:15 am Milan time. I nap for an hour and consider this a huge victory. Six hours later, the plane lands. It is afternoon. Getting off the plane, we are hit by a ferocious wave of hot air. 32°C—that’s nearly 90° for those of you following along in the Bahamas, Belize, the Cayman Islands, Palau, and the United States.

We buy visas to enter the country, and get in line for passport control. We’re hoping the expiring passports and the lack of a yellow fever certificate will not be a problem. Our phones would cost a dollar a minute to use here, so our capabilities for distraction are limited. There is picture-taking. There is fingerprinting. It takes a long time but we get through. The passports are not a problem. The vaccination certificates are not asked for. Huge victory for the visiting team!

As we are finishing up, a German man is taking umbrage at having to be electronically fingerprinted. The passport guy with a big smile, opens his arms, “It is the same for everybody. It is required.” As we move on, the guy continues to argue with passport dudes who have no authority to let him in without fingerprints. Viel Glück, pal.

One of the bags is not showing up. An employee goes out to check. He shows up with it and asks for a “giftie.” Exactly one meter above his head is a sign that says “no tipping.” We are unable to do much anyway. We haven’t had time to get Tanzanian schillings. Outside we zigzag our way through the crowd of drivers holding up paper signs and iPads with mostly western names on them. We find our driver.

We speed off on the left side of the road which, even as a passenger, takes some getting used to. Zanzibar had been a British Protectorate from 1890 to 1963 and retains its driving system. I will go to the wrong side of the car all trip.

Zanzibar begins flashing by. It is green and flat. And poor. We zoom by the houses with tin roofs in various stages of rusting out. Many of the houses have makeshift stands in front of them to sell fruit, vegetables, and other wares. There are building supplies in piles everywhere—recycled brick, gravel, and coral to be mixed with sand and mortar for the foundation and walls. There’s garbage in front of the houses. Not like a dump, but wrappers, cans, old flipflops—stuff that you feel they could clean up in an afternoon if they were presented with a good reason. Of course, in the US, the pollution is harder to detect, often out of plain sight. I obviously don’t read their landscape like they do.

We pull onto a dirt road. A hotel is being built there, our driver tells us, next to the road. It will take years, he says. It will rise up slowly, the day-to-day progress barely noticeable. Perhaps it will be completed by the sons and grandsons of the original workers.

The driver honks and the gate to the resort is opened. The resort is perfect—immaculate, beautiful, a postcard to be snapped in every direction—a juxtaposition to what we’ve seen so far. We meet the owner, a genial German, and his girlfriend, a warm and friendly Zanzibari. Aside from guests, she and their daughters are the only females we will see at the resort. Everything is done by men.

The driver honks and the gate to the resort is opened. The resort is perfect—immaculate, beautiful, a postcard to be snapped in every direction—a juxtaposition to what we’ve seen so far. We meet the owner, a genial German, and his girlfriend, a warm and friendly Zanzibari. Aside from guests, she and their daughters are the only females we will see at the resort. Everything is done by men.

The rest of the day is spent resting and relaxing. It is our first time by the Indian Ocean. I walk toward the surf, instinctively bracing for the water, conditioned by years of living near the numbingly cold Pacific. It’s warmer than body temperature, warmer than expected. It feels strange to swim in.

We eat dinner by the pool. It’s dark but there are lamps standing at each end of the table. We have prepared for mosquitos by purchasing the nastiest Deet spray in all the land, but they prove to be less of a problem than the small quick efficient multitudinous mosquitos Milan produces in the summer. There is a warm breeze which makes the temperature perfect.

We were warned about occasional electric interruptions on Zanzibar, and we are treated to one before the end of the meal. Despite the electric candles on our tables, it gets dark. Really dark. Looking up, we find the stars incredible. Orion is directly above us. The moon is only a sliver, very nearly horizontal. In a few nights, it will be a perfect throne for the Queen of the Night.

The lights return. The girls get dessert. We drink wine. We finish and head to our cabins. It’s been a long day and it’s time to catch up on sleep.

The next day is more of the same. We are not leaving the resort today. We swim. We read and nap by the ocean. We lunch by the beach. We dine by the pool.

The next day, after breakfast, we are off to see the red colobus monkeys. The Jozani forest is filled with red mahogany, palm, eucalyptus, and mangrove trees. Our guide is soft-spoken and knowledgeable. English is not his first language so I cannot ascertain how passionate he is on the subject. But he is earnest and thorough.

The red colobus monkeys are endemic to Zanzibar, and classified endangered. Monkeys hang out near the trail. They aren’t begging—unlike the “wild” monkeys we saw many moons ago on Gibraltar. Those monkeys would turn their noses down at bread the tourists were offering and hold out for potato chips, sometimes ripping bags out of surprised hands. These monkeys seem to be satisfied with attention. They are relaxed and photogenic.

We are taken to a mangrove swamp. We walk on a boardwalk through the forest, over the blackest mud I have ever seen. Our guide hands each of us a long seed pod to drop over the railing into the mud, ideally landing them as if playing a vertical game of lawn darts, thus planting a potential tree. We do not exhibit much prowess in this sport.

As we head back, one monkey, hanging out near our car, has the misfortune of having its branch crack and break, setting off a flurry of desperate flailing and grabbing attempts to right itself. More branches crack. Failing to maintain a modicum of dignity, it unleashes an impressive cacophony of mad monkey cussin’.

The next day, after breakfast, we’re off on a snorkel trip. We zoom through the countryside. Lots of bicycles, lots of people walking down the highway, taking a long walk to somewhere.

Everything is more outside here. It’s no surprise to see three or four people sitting under a tree, by the side of the road, in the middle of nowhere. Or some dudes sitting on a bunch of old tires that are getting a second run in life as outdoor seating. It seems bleak, but I bet they’d do well in a Social Life Head-To-Head with an air-conditioned television-watching all-American family.

The driver slows down to avoid an unmarked speed bump in the road. Calling it a speedbump though is to really undersell the height of the concrete. You could totally teeter a Fiat on top. We are stopped by a couple of uniformed men. Our driver shoots the shit with them in Swahili. Our driver knows them, sees them daily, is allowed to pass. They are just trying to pull in some cash from drivers, he says, especially tourists.

We pull off the highway onto a dirt road, through a small village. We park and walk up to a man who has a pile of gear by a tree, by the beach. The area is the same combination of building materials, candy bar wrappers, and plastic bottles we’ve seen everywhere but at the resort.

There is no whimsically painted “snorkeling tours” sign over the top of a grownup’s lemonade stand here. We arranged the tour through the resort, so the contrast between where we are staying versus the arranged tours is striking. Would the resort go for a more western esthetic in terms of tours if they existed? Would that be a good thing? We are already insulated, in the resort, from the real Zanzibar.

Despite the casual presentation of the snorkeling gear, it all fits and is of decent quality. Getting salt water in your eyes too early in the game, can really put a damper on things. We grab our gear, remove our shoes, and walk through the warm, shallow water out to where the boat is anchored. One of the guys grabs the icebox full of bottled water and soda packed by the resort. The boat has an orange cloth over the top for shade. It is pushed out to a depth where the motor can operate, and we’re off.

We can still see land on one side, but still, the planet has never seemed so round. I finished Life of Pi just a few weeks back. It was easy to imagine how nothing but ocean all around would look.

We arrive at the spot. There are other people there, swimming in circles. It looks like nothing—like a swim area on a lake. We’re just missing the floats and rope to cordon it off.

We gear up, and once we’re in the water, it turns out to be a nice-size reef filled with bright schools of fish. I follow a bunch of yellow and black striped angel fish for twenty minutes. There are some little striped blue ones that have bites out of them. The poor things look like fish and sushi at the same time. After a couple hours, as we swim back to the boat, our guides toss bread into the water and we are suddenly surrounded by hundreds of bright blue fish so crazy for the bread that they ignore us totally.

The next day, the kids are sleeping-in through breakfast and beyond. My wife and I are heading to Stone Town to buy spices at the market. Careening down the road again, there are chickens here and running there. They are quick and lucky. Goats and cows wander everywhere—the house, the field, the road. I can’t imagine that this is communal livestock. The occasional cow is tied to a fence, but mostly they are just let wander. They are not the big fat American cows fed on corn and antibiotics. They are free, and thin, and have a big fatty humps on their backs.

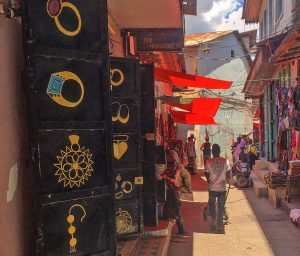

Traveling through a small town, I notice the shops with hand painted names or services. The Beauty salons replace the posters of photographed models with paintings of styled women on the wall next to the door. The signs are all hand-done.

Stone Town is more recognizable to the western eye, with neon signs, billboards, and familiar businesses. I’ve come to an ATM, hoping I can simply get 100 euro out and not accidently withdraw our life savings.

There is no way to view it in Euros but the women at the machine next to me generously volunteers that 300,000 Tanzanian schillings is about 100 euro. I do it, but the number just seems incredibly wrong to me. It gives me thirty 10,000 bills which I think of as €5 bills (the actual amount is €3.60).

Our driver drops us at the market. We exchange numbers and a plan to meet if the phones don’t work. We seem to be the only white people in Stone Town, which is interesting for a minute or so. No one seems to be particularly interested in us either. It’s well over 30° and we are keen to get inside where it is cooler and smells of tea, vanilla, cloves, cinnamon, curry, and cardamom. We immediately attract some guides who want to walk us to their stall and check out their spices. We wave them off for now, and walk through the whole place to get our bearings. We decide that starting with shopping baskets would be good for both now and when we get back to Milan.

Earlier, we had worked out a system for haggling in which I was to be skeptical and stingy, while she expressed interest. This works well on one occasion, and the rest of the time is largely unnecessary. We walk through the market buying tea, gifts, spices, and souvenir-spices. We head outside into the hot narrow streets behind the market, and buy some printed local pants for the girls.

There is so much more to see, not only in Stone Town, but on the whole island. We are, alas, running out of week.

We are up at 2:30. We need to leave at 3. Our flight is at 6. It is quieter than usual. Just a few employees up to see us off. The driver has to be called a couple times, having fallen asleep. The car appears, really not so late.

The gate is opened and we’re off, heading toward the highway, the airport, eventually home. I sit up front beside the driver, having cued to the correct side for the first time all trip. African rap videos play on the dash screen. No sound though. The driver is not watching. So, they’re either for my benefit or he simply hasn’t bothered to turn it off.

We drive fast, perhaps no faster than we did on our daylight trips but it seems faster with Zanzibar coming into view only as the headlights reveal it. The driver is intent, perhaps paying extra attention because he was late and because he is sleepy. The cows and chickens are apparently snoozing well away from the road. Other cars come toward us. The road does not seem wide enough. Both cars will lose side mirrors I think but we are fine. We come to the speed bump, the lone uniformed officer. They talk. Our driver hands a business card over, and we are on our way again.

We arrive at the airport. We tip the driver. We ignore the offers of help. We are budgeting our schillings. Which is good, because at the pre-security suitcase scan, we are discovered to have some shells in one of the suitcases. There is some discussion. Will we have to leave them? Another traveler tells my wife that if we just give the security woman a little something, it’ll be fine. We hand over 10,000 schillings and are on our way.

We check in. The guy loading our bags onto a trolley, points to the destination on the bag . . . to confirm? No, I see by his raised eyebrow that he is asking for a tip. We gave our last schillings to the suitcase lady, so I cannot do anything. As we head to security, I look back to make sure all four suitcases are still on the cart, and heading in the right direction.

For the first time on the trip, we board without trouble. Everyone falls asleep immediately. I look at the movie selection. I bring up the progress map as we fly toward Oman. I read. I nap. I read some more. In Oman, we get Subway and DQ for the girls, and falafel for us. We board the plane. More sleeping (by my wife and daughters). More reading (by me).

We land at Malpensa in the evening, go through passport control. Three of our suitcases appear immediately. Unclaimed suitcases circle slowly, sadly around the carousel, disappear, then reappear again to make another lonely trip around. The amount of people waiting diminishes. We begin making inquiries. I think of our untipped luggage handler in Zanzibar. We fill out paperwork. We try not to dwell. We head toward the car. It is raining and cold. I have only had an hour of sleep but the suitcase drama has reproduced the effects of a caffè doppio.

Two days later, after resigning ourselves to a lost suitcase, the eventual replacement of our daughter’s favorite clothes, and a school computer that shouldn’t have been in there in the first place, we receive notice that the suitcase has been found and is in transit. It arrives. Its contents are intact. Lessons have been learned. Nobody got hurt.

2 Comments

Love this, felt like I was right there with you. Amazing journey!

Thanks! It was fun and there was a whole lotta new. Still more to see.