Two friends have recently reported chance encounters with friends in unlikely places. Cindy ran into an old friend at the Keflavík airport in Iceland, and Megan ran into a friend while traveling in Jordan.

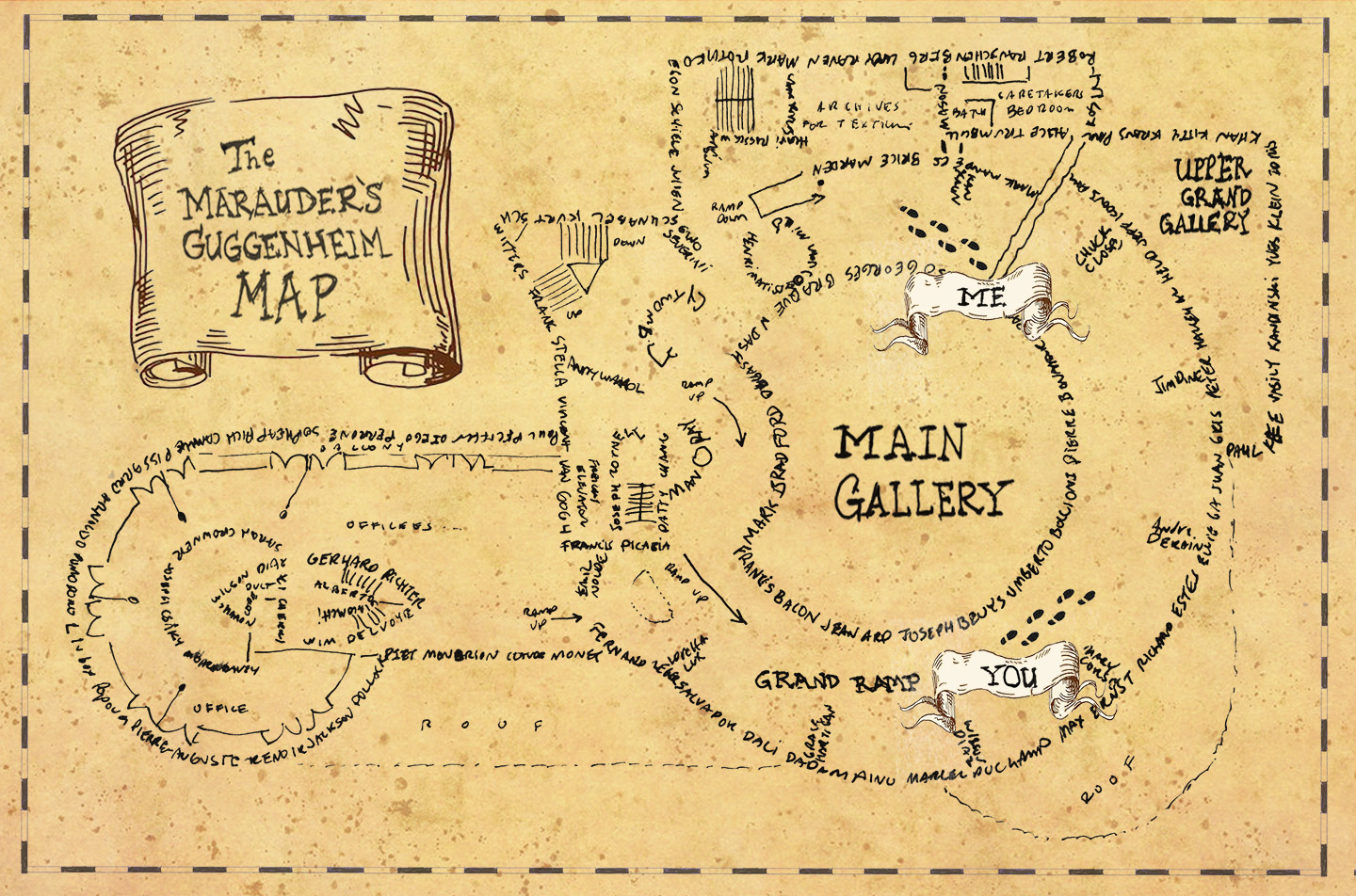

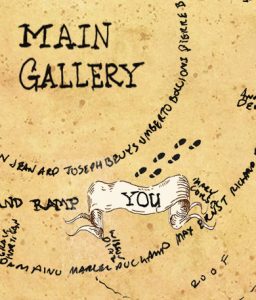

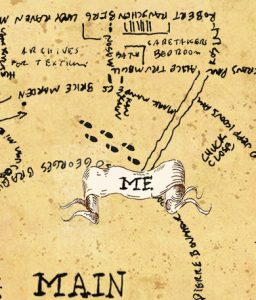

Cindy asked in her post, “What are the chances of meeting a dear friend at an airport in Iceland?” Just this side of impossible to calculate, I’m guessing. The number of the variables alone would explode exponentially in no time. The odds of running into someone are different if you’re at the Keflavík airport, the Guggenheim Museum, or walking on the Great Wall. We might very well have been within a few feet of each other at Grand Central Station, but the sheer number of people there surely diluted our chances of meeting. And what number of friends, dear or otherwise, would you choose to plug into such an equation?

To sum up what happens to make these unlikely meetings possible:

- You are at the same place—which ideally is wildly out of the context you know them in

- You’re there at the same time—and the longer it’s been since you’ve been at the same place at the same time, the better.

- At least one of you needs to be aware of their surroundings—if you both have your noses pointed toward your phones, forget about it

- You need to be able to recognize each other—how long has it been after all?

- You both want to be seen—some of us aren’t so keen on getting a blast from the past

So being away in an exotic locale and running into an old friend happens pretty rarely. But I’m wondering how many times we just miss one of these chance encounters.

How many times are we just a block away from each other? Or maybe one of us was there in the same place, having their photo taken in front of the same landmark, an hour earlier.

If we were to expand our range from “same place, same time,” to “same block, same hour,” then the chances must go up considerably. The odds that there could be someone we know with a block or an hour of us, would have to

If we were to expand our range from “same place, same time,” to “same block, same hour,” then the chances must go up considerably. The odds that there could be someone we know with a block or an hour of us, would have to

be greater than the odds of running into them—since this happens only occasionally—and it would stand to reason that more often we just miss people we’d like to run into. Maybe we’ve walked right by each other because at least one of us is looking at a map or a view or a Kandinsky.

Louis Pasteur once wrote that “Chance favors the prepared mind,” so maybe we can look at what we can do to improve our chances of running into an old friend somewhere.

Short of having Harry Potter’s Marauder’s Map (it would have to be specially enchanted to filter out creepy intentions) to identify friends in the immediate vicinity, or neurotically checking in to places on Facebook, we’ll just have to count on luck—which makes for better magic anyway.

Our best chances then lie with noticing people already in the same place at the same time.

So first things first, you need to put your phone away. I know, I know. But really. All the world is made apparent to us via our perceptions. It’s already being filtered through our senses and brains before it reaches us—the world isn’t going to seem bigger and more interesting if you send it through more funnels—the news as interpreted, written, edited, published, shared, and finally viewed on your phone on the steps of the Taj Mahal, while your best friend from 6th grade walks by, googling for a restaurant on her phone.

“All day long, you are selectively paying attention to something, and much more often than you may suspect, you can take charge of this process to good effect. Indeed, your ability to focus on this and suppress that is the key to controlling your experience and, ultimately, your well-being.”

—Winifred Gallagher, Rapt

I was recently at the Linate airport in Milan, waiting to pick up my daughter. As I looked through the faces, ready to pick out hers, people coming through the gate started reminding me of friends and acquaintances—this person’s eyes, that person’s hair, the way that guy walked. One woman looked so much like a nanny the girls had a few years ago, I had to do a double take—it was not her but it absolutely could have been an older sister.

I was recently at the Linate airport in Milan, waiting to pick up my daughter. As I looked through the faces, ready to pick out hers, people coming through the gate started reminding me of friends and acquaintances—this person’s eyes, that person’s hair, the way that guy walked. One woman looked so much like a nanny the girls had a few years ago, I had to do a double take—it was not her but it absolutely could have been an older sister.

Our brains are wired to recognize faces—one of our oldest skills, in fact. “At as early as four months,” Max McClure writes on the Stanford website, “babies’ brains already process faces at nearly adult levels, even while other images are still being analyzed in lower levels of the visual system.” So even if a few decades have passed since we last saw a friend, our face-recognition ability gives us a very good chance of spotting them, but you have to put down your phone and pay attention. Even if you don’t spot anyone you know, people watching is way more interesting than anything up on the Huffpost right now.